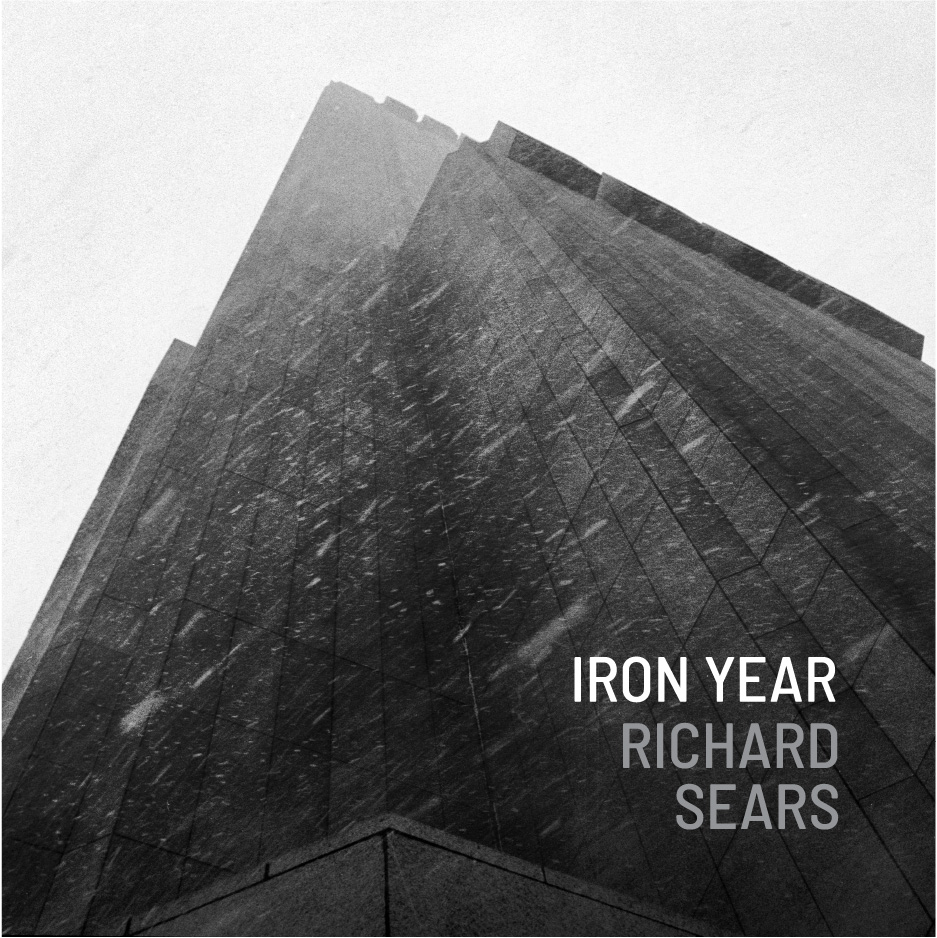

Iron Year

– Excerpt from “To Brooklyn Bridge” –

by Hart Crane, 1933

O harp and altar, of the fury fused,

(How could mere toil align thy choiring strings!)

Terrific threshold of the prophet’s pledge,

Prayer of pariah, and the lover’s cry,

Again the traffic lights that skim thy swift

Unfractioned idiom, immaculate sigh of stars,

Beading thy path—condense eternity:

And we have seen night lifted in thine arms.

Under thy shadow by the piers I waited

Only in darkness is thy shadow clear.

The City’s fiery parcels all undone,

Already snow submerges an iron year …

O Sleepless as the river under thee,

Vaulting the sea, the prairies’ dreaming sod,

Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend

And of the curveship lend a myth to God.

Liner Notes, by Vikram Devasthali, 2018

“They took your life apart, and called your failures art.

They were wrong, though they won’t know ‘til tomorrow.”

Elliott Smith, “Tomorrow, Tomorrow”

Why do we do it?

There are artists who consider the question insulting. As the candy shop owner in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory admonishes one of his young customers, “do you ask a fish how it swims? Or a bird how it flies? No siree, you don’t! They do it because they were born to do it.” Art, in this view, is more of a calling than a profession. The artist merely answers the call; indeed, she can do nothing else. Underneath the lofty rhetoric of this school of thought lies the sinister implication that the artistic impulse is, in a sense, sociopathic. To the extent that the artist is a benefit to anyone, it is only by accident; she is deaf to all concerns that don’t relate to her muse. Given that the cult of the mad artist seems to have as many followers as ever, it’s not at all clear that most people would object to such a characterization. Even the uninitiated would have to agree that art is preferable as a manifestation of insanity to, say, mass murder.

Assuming, however, that sociopathy is no more prevalent among artists than it is in any other community, there is always the resort to love. Art is a tangible manifestation of the artist’s love, and his fellow humans are transformed by his love when they experience his art. This explanation stands up tolerably well at the heights of artistic accomplishment, but meets with turbulence at lower altitudes. What are we to think of the artist who doggedly persists in making art that is uplifting to precisely no one? Perhaps it’s rude to press him about it, and we might even admire his tenacity. Still, it would not be entirely impertinent to suggest that such an artist is robbing the world of the work he might be doing if he turned his back on his love. Some societies have the resources to comfortably accommodate this kind of wasteful effort, but many do not. Yet there are bad artists everywhere, and they do not seem to be unduly scorned by their neighbors. Well, maybe just by their neighbors.

Lately, a new argument has been gaining currency: that art is good for you. Art appreciation and participation improves brain development and test scores. Act now, and you might even get a date for prom! Yo-Yo Ma argues that the push for more instruction in STEM – Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics – should be complimented with more arts instruction to make STEAM. It’s a catchy acronym, but this line of thought begs some questions. What if there are better ways to improve brain development? And what if spending more time on art boosts students’ math scores, but not as much as spending more time on math? Most troubling of all, even the kids who don’t care about art seem to find someone to go to prom with them. The proponents of this approach to arts advocacy have the best of intentions, but it seems self-evident that artists are driven by motivations that have nothing to do with providing some sort of high-brow makeover to grade-schoolers.

So if we’re not compelled to do it, and if love is not all we need, and if art isn’t necessarily as good for us as advertised, then why do we do it? Because we can. It is the height of arrogance to think that we can, in the words of Hart Crane, “lend a myth to god,” but we can and – once in a great while – we do. Crane had in mind the grandeur of Brooklyn Bridge, the subject of one of the great dad jokes of yesteryear. For example: “I’ve been told I look like a movie star. And if you believe that, there’s a bridge in Brooklyn I’d like to sell you.” Like all good dad jokes, it has a simple and a deep meaning. The simple meaning, in case you missed it, is that the speaker does not own Brooklyn Bridge. The deeper meaning has to do with the innate absurdity of the thought that Brooklyn Bridge could be owned, or bought, or sold. And though it’s not really absurd – people designed it, built it and paid for it – we can relate to Crane’s awe. “(How could mere toil align thy choiring strings!),” he marvels.

The Gospels tell of a woman from Bethany who anointed Jesus with expensive oil. His disciples were aghast; the woman should have sold the oil and given the money to the poor, they complained. Jesus retorts that “ye have the poor always with you; but me ye have not always.” What he seems to mean is this: too much devotion to a principle, even one as noble as charity, drains the sweetness out of life. It robs the less fortunate of the better world into which we should all work to usher them. The woman from Bethany was not compelled to be kind, and though she loved Jesus, it was not her love that purchased the oil. Nor did she have any hope, by her actions, of preventing the horrible fate that awaited him. She did what she did because she could, and her simple act of defying inertia became a work of art for all time. Whether it’s God’s work or the height of self-indulgence is a question for theologians and philosophers to wrestle with. In the meantime, “the world tastes good ‘cause the candy man thinks it should.”

Vikram Devashthali, 2018